What Animals Fought In The Colosseum Bear Vs Lion

Could You Stomach the Horrors of 'Halftime' in Ancient Rome?

Cristin O'Keefe Aptowicz is a New York Times acknowledged nonfiction writer and poet, and the author of " Dr. Mütter's Marvels: A Truthful Tale of Intrigue and Innovation at the Dawn of Modern Medicine" (opens in new tab) (Avery, 2014), which made vii national "Best Books of 2014" lists, including those from Amazon, The Onion's AV Club, NPR'southward Science Friday and The Guardian, among others. Aptowicz contributed this sectional commodity to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights .

The enormous loonshit was empty, relieve for the seesaws and the dozens of condemned criminals who sat naked upon them, hands tied behind their backs. Unfamiliar with the recently invented contraptions known as petaurua, the men tested the seesaws uneasily. One criminal would push off the footing and suddenly find himself fifteen anxiety in the air while his partner on the other side of the seesaw descended swiftly to the basis. How strange.

In the stands, tens of thousands of Roman citizens waited with half-bored curiosity to run into what would happen adjacent and whether it would be interesting plenty to proceed them in their seats until the side by side part of the "large show" began.

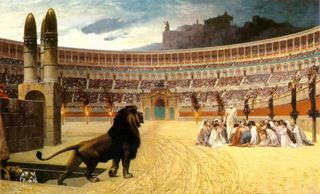

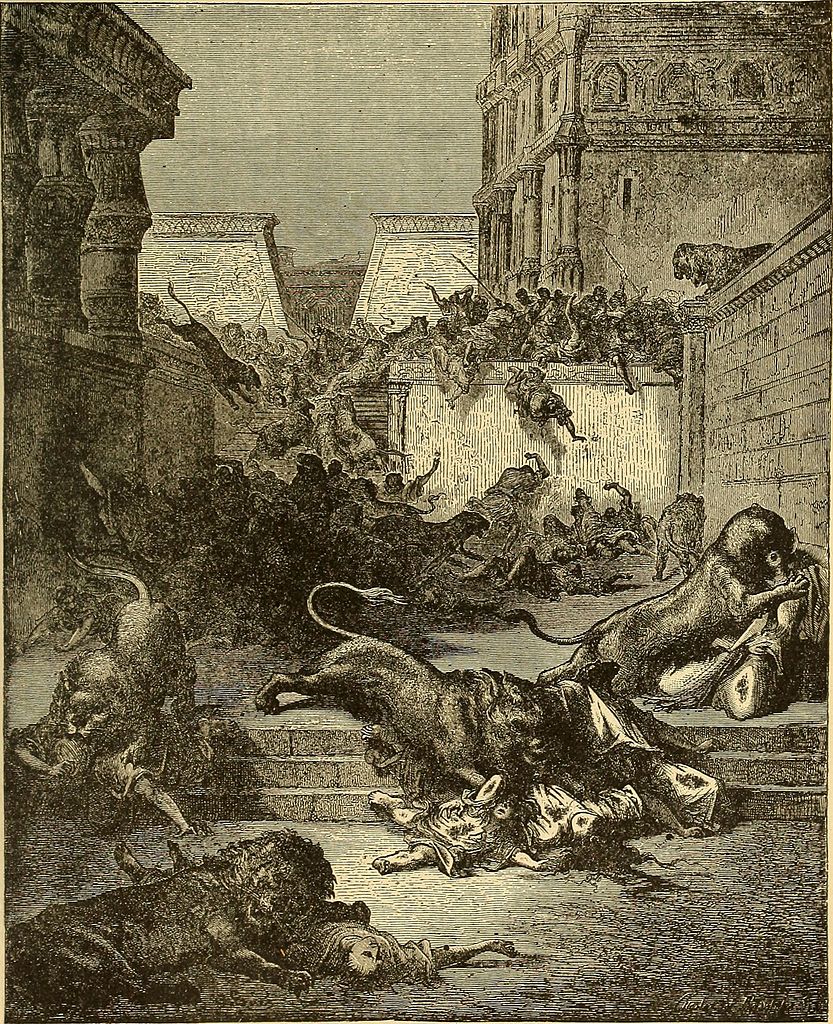

With a flourish, trapdoors in the flooring of the arena were opened, and lions, bears, wild boars and leopards rushed into the arena. The starved animals bounded toward the terrified criminals, who attempted to spring away from the beasts' snapping jaws. But equally one helpless man flung himself upwardly and out of harm's way, his partner on the other side of the seesaw was sent crashing downward into the seething mass of claws, teeth and fur.

The crowd of Romans began to express mirth at the dark antics before them. Presently, they were clapping and yelling, placing bets on which criminal would die kickoff, which i would last longest and which i would ultimately be chosen by the largest lion, who was still prowling the outskirts of the arena's pure white sand.

And with that, another "halftime show" of damnatio ad bestias succeeded in serving its purpose: to keep the jaded Roman population glued to their seats, to the delight of the event's scheming organizer.

Welcome to the show

The Roman Games were the Super Basin Sundays of their time. They gave their ever-changing sponsors and organizers (known as editors) an enormously powerful platform to promote their views and philosophies to the widest spectrum of Romans. All of ancient Rome came to the Games: rich and poor, men and women, children and the noble elite alike. They were all eager to witness the unique glasses each new game promised its audience.

To the editors, the Games represented ability, money and opportunity. Politicians and aspiring noblemen spent unthinkable sums on the Games they sponsored in the hopes of swaying public opinion in their favor, courting votes, and/or disposing of any person or warring faction they wanted out of the way.

The more extreme and fantastic the spectacles, the more popular the Games with the full general public, and the more popular the Games, the more influence the editor could have. Because the Games could make or break the reputation of their organizers, editors planned every terminal detail meticulously.

Thanks to films like "Ben-Hur (opens in new tab)" and "Gladiator (opens in new tab)," the two most popular elements of the Roman Games are well known even to this mean solar day: the chariot races and the gladiator fights. Other elements of the Roman Games have likewise translated into mod times without much change: theatrical plays put on past costumed actors, concerts with trained musicians, and parades of much-cared-for exotic animals from the city'south private zoos.

But much less discussed, and indeed largely forgotten, is the spectacle that kept the Roman audiences in their seats through the sweltering midafternoon rut: the blood-spattered halftime show known as damnatio ad bestias — literally "condemnation by beasts" — orchestrated by men known as the bestiarii.

Super Bowl 242 B.C: How the Games Became So Brutal

The cultural juggernaut known as the Roman Games began in 242 B.C., when two sons decided to celebrate their father's life past ordering slaves to battle each other to the expiry at his funeral. This new variation of ancient munera (a tribute to the expressionless) struck a chord within the developing republic. Before long, other members of the wealthy classes began to incorporate this blazon of slave fighting into their ain munera. The practise evolved over time — with new formats, rules, specialized weapons, etc. — until the Roman Games as we now know them were born.

In 189 B.C., a delegate named M. Fulvius Nobilior decided to do something unlike. In addition to the gladiator duels that had become common, he introduced an creature human action that would see humans fight both lions and panthers to the death. Big-game hunting was not a role of Roman civilization; Romans only attacked big animals to protect themselves, their families or their crops. Nobilior realized that the spectacle of animals fighting humans would add a inexpensive and unique flourish to this fantastic new pastime. Nobilior aimed to make an impression, and he succeeded.

With the nascence of the outset "animal program," an uneasy milestone was accomplished in the development of the Roman Games: the point at which a human beingness faced a snarling pack of starved beasts, and every laughing spectator in the oversupply chanted for the large cats to win, the point at which the commonwealth's obligation to make a man'due south death a fair or honorable one began to exist outweighed by the entertainment value of watching him die.

20-2 years later, in 167 B.C., Aemlilus Paullus would requite Rome its first damnatio ad bestias when he rounded upward army deserters and had them crushed, ane past i, under the heavy feet of elephants. "The act was washed publicly," historian Alison Futrell noted in her book "Blood in the Arena (opens in new tab)," "a harsh object lesson for those challenging Roman authority."

The "satisfaction and relief" Romans would experience watching someone considered lower than themselves be thrown to the beasts would get, as historian Garrett G. Fagan noted in his volume "The Lure of the Arena (opens in new tab)," a "cardinal … facet of the experience [of the Roman Games. … a feeling of shared empowerment and validation … " In those moments, Rome began the transition into the self-indulgent decadence that would come up to define all that we associate with the great society's demise.

The Role of Julius Caesar

General Julius Caesar proved to be the first true maestro of the Games. He understood how these events could be manipulated to inspire fearfulness, loyalty and patriotism, and began to stage the Games in new and ingenious ways. For example, Caesar was the start to suit fights between recently captured armies, gaining firsthand cognition of the fighting techniques used by these conquered people and providing him with powerful insights to aid future Roman conquests, all the while demonstrating the democracy's own superiority to the roaring crowd of Romans. After all, what other city was powerful enough to command foreign armies to fight each other to the decease, solely for their viewing pleasance?

Caesar used exotic animals from newly conquered territories to brainwash Romans nigh the empire'due south expansion. In one of his games, "Animals for Show and Pleasance in Ancient Rome (opens in new tab)" author George Jennison notes that Caesar orchestrated "a hunt of 4 hundred lions, fights between elephants and infantry … [and] bull fighting past mounted Thessalians." After, the first-ever giraffes seen in Rome arrived — a gift to Caesar himself from a love-struck Cleopatra.

To execute his very specific visions, Caesar relied heavily on the bestiarii — men who were paid to house, manage, breed, train and sometimes fight the bizarre menagerie of animals collected for the Games.

Managing and preparation this ever-changing influx of beasts was non an easy task for the bestiarii. Wild fauna are born with a natural hesitancy, and without grooming, they would commonly cower and hibernate when forced into the arena'due south center. For example, it is not a natural instinct for a lion to attack and swallow a human beingness, let alone to practise and so in front of a crowd of 100,000 screaming Roman men, women and children! And withal, in Rome's ever-more-violent civilisation, disappointing an editor would spell certain death for the low-ranking bestiarii.

To avoid being executed themselves, bestiarii met the challenge. They developed detailed training regimens to ensure their animals would human activity as requested, feeding arena-built-in animals a nutrition compromised solely of human flesh, breeding their best animals, and allowing their weaker and smaller stock to be killed in the arena. Bestiarii even went and then far as to instruct condemned men and women on how to conduct in the ring to guarantee a quick decease for themselves — and a better testify. The bestiarii could leave zero to take chances.

As their reputations grew, bestiarii were given the power to independently devise new and even more audacious spectacles for the ludi meridiani (midday executions). And by the time the Roman Games had grown popular enough to make full 250,000-seat arenas, the work of the bestiarii had become a twisted art form.

As the Roman Empire grew, so did the ambition and arrogance of its leaders. And the more arrogant, egotistic and unhinged the leader in power, the more spectacular the Games would get. Who better than the bestiarii to assist these despots in taking their version of the Roman Games to new, ever-more grotesque heights?

Caligula Amplified the Cruelty

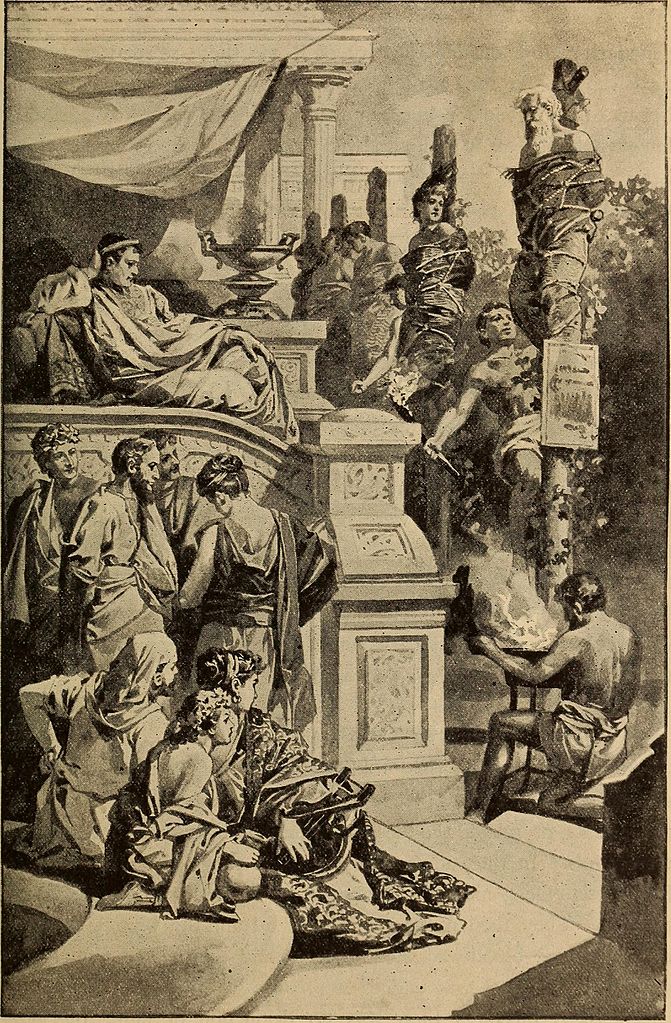

Fauna glasses became bigger, more elaborate, and more flamboyantly cruel. Damnatio ad bestias became the preferred method of executing criminals and enemies alike. So important where the bestiarii's contribution, that when butcher meat became prohibitively expensive, Emperor Caligula ordered that all of Rome'south prisoners "exist devoured" by the bestiarii's packs of starving animals. In his masterwork De Vita Caesarum, Roman historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (b. 69 A.D.) tells of how Caligula sentenced the men to death "without examining the charges" to see if decease was a fitting penalty, just rather past "merely taking his identify in the middle of a colonnade, he bade them be led away 'from baldhead to baldhead,'"(It should too exist noted that Caligula used the funds originally earmarked for feeding the animals and the prisoners to construct temples he was building in his ain honor!)

To run across this ever-growing force per unit area to keep the Roman crowds happy and engaged by bloodshed, bestiarii were forced to consistently invent new means to kill. They devised elaborate contraptions and platforms to give prisoners the illusion they could salve themselves — only to have the structures collapse at the worst possible moments, dropping the condemned into a waiting pack of starved animals. Prisoners were tied to boxes, lashed to stakes, wheeled out on dollies and nailed to crosses, and then, prior to the animals' release, the action was paused so that bets could be made in the crowd virtually which of the helpless men would be devoured first.

Perchance most popular — as well as the most difficult to pull off — were the re-creations of death scenes from famous myths and legends. A single bestiarius might spend months training an eagle in the art of removing a thrashing man's organs (a la the myth of Prometheus).

The halftime evidence of damnatio ad bestias became and then notorious that it was common for prisoners to attempt suicide to avoid facing the horrors they knew awaited them. Roman philosopher and statesmen Seneca recorded a story of a German prisoner who, rather than be killed in abestiarius' show, killed himself by forcing a communally used prison lavatory sponge down his pharynx. 1 prisoner who refused to walk into the arena was placed on a cart and wheeled in; the prisoner thrust his own head betwixt the spokes of its wheels, preferring to break his own neck than to face whatsoever horrors the bestiarius had planned for him.

It is in this era that Rome saw the rise of its about famous bestiarius, Carpophorus, "The Rex of the Beasts."

The Rising of a Beast Master

Carpophorus was celebrated not only for training the animals that were set up upon the enemies, criminals and Christians of Rome, merely also for famously taking to the center of the arena to battle the most fearsome creatures himself.

He triumphed in i friction match that pitted him against a bear, a lion and a leopard, all of which were released to attack him at in one case. Another time, he killed 20 divide animals in one battle, using just his blank hands as weapons. His power over animals was and so unmatched that the poet Martial wrote odes to Carpophorus.

"If the ages of old, Caesar, in which a barbarous globe brought along wild monsters, had produced Carpophorus," he wrote in his best known work, Epigrams. "Marathon would not accept feared her balderdash, nor leafy Nemea her lion, nor Arcadians the boar of Maenalus. When he armed his hands, the Hydra would have met a single expiry; i stroke of his would have sufficed for the entire Chimaera. He could yoke the fire-bearing bulls without the Colchian; he could conquer both the beasts of Pasiphae. If the ancient tale of the sea monster were recalled, he would release Hesione and Andromeda single-handed. Let the glory of Hercules' achievement exist numbered: information technology is more to have subdued twice ten wild beasts at one time."

To accept his work compared so fawningly to battles with some of Rome'southward nigh notorious mythological beast sheds some light on the astounding work Carpophorus was doing within the arena, merely he gained fame besides for his beast work behind the scenes. Perhaps almost shockingly, information technology was said that he was among the few bestiarii who could control animals to rape man beings, including bulls, zebras, stallions, wild boars and giraffes, among others. This crowd-pleasing trick allowed his editors to create ludi meridiani that could non but combine sex and decease merely also claim to be honoring the god Jupiter. Subsequently all, in Roman mythology, Jupiter took many animal forms to have his mode with human women.

Historians still debate how common of an occurrence public bestiality was at the Roman Games — and especially whether forced bestiality was used as a course of execution — but poets and artists of the time wrote and painted about the spectacle with a shocked awe.

"Believe that Pasiphae coupled with the Dictaean balderdash!" Martial wrote. "We've seen it! The Aboriginal Myth has been confirmed! Hoary antiquity, Caesar, should non marvel at itself: whatsoever Fame sings of, the loonshit presents to you lot."

The 'Gladiator' Commodus

The Roman Games and the work of the bestiarii may have reached their noon during the reign of Emperor Commodus, which began in 180 AD. By that fourth dimension, the human relationship between the emperors and the Senate had disintegrated to a bespeak of virtually-consummate dysfunction. The wealthy, powerful and spoiled emperors began interim out in such debauched and deluded ways that even the working form "plebs" of Rome were unnerved. But even in this heightened environment, Commodus served equally an extreme.

Having piffling interest in running the empire, he left most of the day-to-day decisions to a prefect, while Commodus himself indulged in living a very public life of immoderacy. His harem contained 300 girls and 300 boys (some of whom it was said had so bewitched the emperor as he passed them on the street that he felt compelled to order their kidnapping). But if at that place was one affair that allowable Commodus' obsession above all else, it was the Roman Games. He didn't just want to put on the greatest Games in the history of Rome; he wanted to be the star of them, too.

Commodus began to fight equally a gladiator. Sometimes, he arrived dressed in lion pelts, to evoke Roman hero Hercules; other times, he entered the band admittedly naked to fight his opponents. To ensure a victory, Commodus only fought amputees and wounded soldiers (all of whom were given but flimsy wooden weapons to defend themselves). In ane dramatic case recorded in Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Commodus ordered that all people missing their feet be gathered from the Roman streets and exist brought to the arena, where he commanded that they exist tethered together in the crude shape of a human trunk. Commodus and so entered the loonshit's center ring, and clubbed the entire group to death, before announcing proudly that he had killed a giant.

But being a gladiator wasn't enough for him. Commodus wanted to rule the halftime testify as well, so he set nigh creating a spectacle that would feature him equally a great bestiarius. He not but killed numerous animals — including lions, elephants, ostriches and giraffes, among others, all of which had to be tethered or injured to ensure the emperor's success — simply as well killed bestiarii whom he felt were rivals (including Julius Alexander, a bestiarius who had grown dearest in Rome for his power to kill an untethered king of beasts with a javelin from horseback). Commodus in one case fabricated all of Rome sit down and watch in the blazing midday sun as he killed 100 bears in a row — and so made the city pay him 1 millions esterces (ancient Roman coins) for the (unsolicited) favor.

By the time Commodus demanded the city of Rome exist renamed Colonia Commodiana ("Urban center of Commodus") —Scriptores Historiae Augustae, noted that not but did the Senate "pass this resolution, but … at the same time [gave] Commodus the name Hercules, and [called] him a god" — a conspiracy was already afoot to impale the mad leader. A motley crew of assassins — including his court chamberlain, Commodus' favorite concubine, and "an athlete called Narcissus, who was employed every bit Commodus' wrestling partner" — joined forces to impale him and end his unhinged reign. His death was supposed to restore balance and rationality to Rome — but it didn't. By then, Rome was broken — bloody, chaotic and unable to cease its death spiral.

In an ultimate irony, reformers who stood upwardly to oppose the civilization's violent and debauched disorder were often punished past death at the easily of the bestiarii, their deaths cheered on by the very same Romans whom they were trying to protect and save from destruction.

The Decease of the Games and the Rise of Christianity

As the Roman Empire declined, then did the size, scope and brutality of its Games. Even so, information technology seems fitting that one of the nigh powerful seeds of the empire'due south downfall could be establish inside its ultimate sign of antipathy and power — the halftime show of damnatio advert bestias.

Early on Christians were among the most popular victims in ludi meridiani. The emperors who condemned these men, women and children to public decease by beasts did and then with the obvious hope that the spectacle would be so horrifying and humiliating that it would discourage any other Romans from converting to Christianity.

Little did they realize that the tales of brave Christians facing certain death with grace, ability and humility made them some of the earliest martyr stories. Nor could they have imagined that these frequently-repeated narratives would so serve equally invaluable tools to drive more people toward the Christian faith for centuries to come.

In the finish, who could have always imagined that these near-forgotten "halftime shows" might testify to have a more lasting impact on the world than the gladiators and chariot races that had overshadowed the bestiarii for their unabridged being?

Read more from Aptowicz in her Expert Voices essay, " Surgery in a Time Before Anesthesia ."

Follow all of the Skilful Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and practise not necessarily reverberate the views of the publisher. This version of the commodity was originally published on Live Scientific discipline.

Source: https://www.livescience.com/53615-horrors-of-the-colosseum.html

Posted by: brownefolisn.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Animals Fought In The Colosseum Bear Vs Lion"

Post a Comment